Sunday, September 29, 2024

Judges: Chapter 10

Sunday, June 23, 2024

Judges 5: In Writing

I, to God, I will sing

Seek "I"

pasty-faced in the mirror

while hands drum the door

Imma, I need you, I really

need you.

Nur, nur, the baby pinches my shin

demanding milk.

From the corner of my eye

the hawk-swoop of my son's hand

and my daughter is wailing.

Motherhood is resisting

the blandishment

of rest. Constant

vigilance.

Pull your mouth into a smile

Focus. Split

your ears three ways.

Why did you hit your sister?

my voice a harsh caw.

The casual kicks

swats and biting. Stop

I say. I am counting

They are wildwaters

bursting all dams

I the melting mountain.

His legs kick

like a donkey's, just missing

my stomach,

I wonder how i ever

contained him

within me.

Peer through the window

as the last lights fades

enumerate and engrave the finds of the day:

a smile, a cloud, a bird, glints on water

try to awaken tomorrow

to eke out a voice

and tell it sing.

Sunday, June 9, 2024

Judges: Chapter 2

Monday, May 27, 2024

A Belated Goodbye to Joshua

It feels strange to say “Goodbye to Joshua” when I have just said a new “hello.”

After

several years (!), I can't even begin to understand or explain what made me stop the Joshua section one chapter before completion.

I

do remember after the end of Deuteronomy, I felt like I had reached closure, a

natural stop point. Joshua always felt like a tag-along, an added experiment. I

experienced the Book of Joshua as a comedown after the high poetry and complex

narratology of Deuteronomy—the language mundane, the violence off-putting. And

as a first-time new mother, I also had other concerns that felt more urgent. Yet

why I stopped right before the end, I can’t say. No doubt there were some deep,

unacknowledged currents there. I do know that the longer I waited, the more

distant I felt from the project, and the harder it became to go back. Finally I

blocked it out. A niggling untied end that I refused to consider.

Then came this year’s terrible Simchat Torah and its aftermath. As October turned to

November, November to December, month after month, the war raging on with no exit

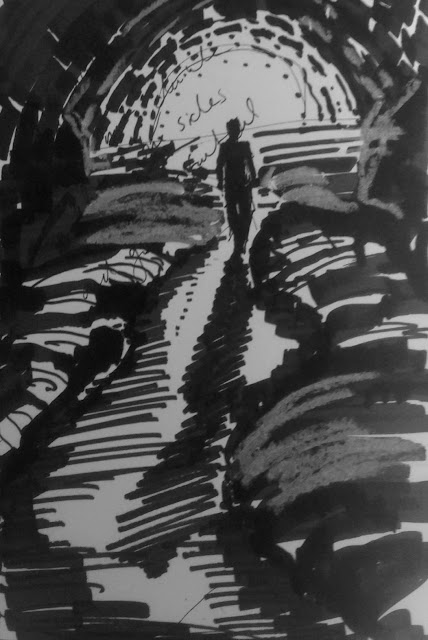

point, I found myself completely blocked. Words disappeared. When I tried to draw, I had to push against

the intractable weight of futility. It was as bad—worse—as the block that started me on the Bibliodraw project so many years ago. This time I didn’t have

whiplash or amnesia. My arm was working. It was my heart that wasn’t. I found myself

desperate for a daily project. And the only project that seemed real enough and

urgent enough to matter was Bibliodraw—a project in which I had already

invested so much, a project embodying so many layers and history. It is also a project that gives me a framework

of feeling my way through this desperate time. Feeling my way, as I always have,

with the “tikvat hut ha-shani”, Rahab’s guiding bright thread of central

archetypal narratives. Returning to Bibliodraw is returning to the questions:

what are we doing here? How do we earn this home? How do we lose it? A project

that could engage my heart and intellect and hand as one.

Finding

a quiet moment does not happen often with four little kids in war time. But I suddenly

had a day when I woke up, and all my children were in childcare, and I had no urgent

projects that I needed to complete. For the first time in what seemed like months,

I drew a deep breath. And I said: I'm going to finish this. I will at least

complete Joshua, and close this one circle. Tie up this one dangling thread.

Because,

despite all my denials, it was still bothering me. The notebook there, sitting

in my closet, incomplete. And so I spent my quiet day reading through Joshua

again. This is a much more condensed process that my other “goodbyes”, which

were the slow accumulation of weeks' worth of ruminations and thoughts. This

rather is the result of months of studying, years of silence, then a quick one-day

review

So,

the those thoughts after this review.

The

Book of Joshua opens with a promise and a charge: I will be with you like I was

with Moses, but you must take courage and be strong. The book indeed continues

directly from the story of Moses, providing a bridge from Deuteronomy, . Yet it

also actively redoes Moses’ legacy in a complex balancing act. Jooshua’sleadership begins with crossing the Jordan, in a conscious recreation of the parting of the Red Sea. This places him

in the position of Moses, even as it rebirths Israel yet again as a nation. This

is a new generation, with a new destiny.

Israel then camps in Gilgal, where they recreate the Exodus, celebrating Passover. It

is a place of renewed literal brit, reactivating circumcision after the years

of wandering: “Make thee knives of flint, and circumcise again the children of

Israel the second time. … them [the children born in the desert] did Joshua

circumcise; for they were uncircumcised, because they had not been circumcised

by the way.” The desert era is seen as a hiatus, a kind of suspended animation

between the beginning of the journey and its end. It is only now, when the

children of Israel camp in Gilgal that they start national life anew

The ideas originally presented by Moses in the desert, which existed

until this point only in words and concept, are now put into action, finding embodiment

in the concrete space of the Land: cities of refuge, covenants in specific

places, words literally etched in stone. Yet embodiment is a dynamic and gradual process. Ideas become real, but

not at once. Repetition and variation are key elements as this book. We keep

going back to revisit history, even as we move forward. There is aonstant tension between potential and actual, becoming and being. The virtual desert

journey does not truly end.

Again and

again the verses declare that the conquest is complete, that the land is “subdued”,

that Israel is settled and secure. Again and again, we find that it is not so.

The same cities are conquered and unconquered, again and again: Hebron,

Debir. This tension is perfectly encapsulated at the end of the era, when

Joshua sends out representatives of eeach of the tribes to scout out and demarcatethe boundaries of their estate (18: 4). The land is then “distributed…each to

his inheritance” (19:49), and they make “and end of dividing the land’ (19:

51), even though, as we find out, the land is as yet mostly unconquered, and

not yet theirs to divide. The inheritance “ends” in abstracted visualization, even

as in concrete terms it remains undone.

Throughout

this intense period of process, Gilgal is the home base, from which Israel sets

out in short sorties, returning back to this space of covenant, as they try to

work out the relationship between themselves and God.

The

conquest begins with thedivine battle at with Jericho, which is essentially a version

of the Jubilee (yovel): seven cycles on the seventh day, which ends with

the blowing of the shofar (yovel), in a recreation of the Jubilee

opening which undoes human ownership. With the blowing of the Jubilee horn, all

the land returns to the owners originally allotted by God, all debts are

cancelled, human possession and transactions are undone. We return to origin. Just so, Israel’s inheritance

of the land begins with God announcing a Jubilee, undoing the ownership of the Canaanites.

The yovel is blown, the land returns to God. The victory is not the people’s

,but completely herem—forbidden, within the realm of the divine.

The

second battle with Ai opens the door for human involvement in battle, as God

steps back, acting mostly as tactician. And throughout the book, Joshua pushing

for greater and greater human involvement. “You are a great people, who have

great power…you shall drive out the Canaanites” (17:17), he tells the children

of Joseph, urging them to take charge of their inheritance.

Sunday, May 26, 2024

Joshua: Chapter 24

God of faithfulness and choice

He is your belonging

in a land not your own

and the cycles close

Monday, May 7, 2018

Joshua: Chapter 23

Sunday, November 5, 2017

Joshua: Chapter 8

Tuesday, January 26, 2016

Deuteronomy 33: In Writing

Wednesday, January 13, 2016

Deuteronomy: Chapter 32

Despite the duality of the poem, there is also a drive to unity, an undermining of the binary split. The vegetable becomes animal, dripping blood, full of fat; stones seep honey and water, as the world is poetically tied into a single entity. God, in the poem, represents the "straight" unchanging line that runs through history, while Israel is "a twisted generation," changing and turning as the years pass. Yet this torturous "vine" circles around the solidity of God's rock.

The poem ends by declaring that God holds within Himself both opposing forces "I kill and I make alive, I wounded and I heal." There are no two sides, only a single reality: "I am He...there is none that can deliver from My hands."

Sunday, January 3, 2016

Deuteronomy: Chapter 31

Who crosses to the other side ?

Write the words

and make them live

on the ears

on the tongue...

[For full chapter, click here

"Behold, the day approaches that you must die." With this chapter, we arrive at the final section of the book: the death of Moses. Again and again, the word tum'am, "closing, ending, completion" is repeated. We have come to the final day of Moses' life: "I am one hundred and twenty years old today. I am no longer able to come and go."

With Moses unable to "cross" ('a'v'r--another key word of the chapter), he now "goes" to attempt to provide for continuity. First, he passes the mantle on to Joshua, who can "cross before you." Joshua will be the emissary who will "come with you" into the land, a physical continuation of Moses leadership. The next tack of preservation is writing. If the Book of Numbers focused on learning how to speak, this Book of Words (the literal meaning of the Hebrew name, Devarim) ends with a focus on how to write: "And Moses wrote this teaching (torah) and delivered it to the priests and the sons of Levi...and the elders of Israel" (31:9). This is a writing that is meant for reading, a code being lain down for public transmission: "you will read this teaching before all of Israel, in their ears. Gather the people together: men women, and children and the stranger within your gates, that they may hear and may learn... so that their children, who do not know, may hear and learn" (10-13). Through this writing, Moses' teaching will live on, to be heard by later generations who do not "know" Sinai.

God responds to Moses' "going" by calling him to come "stand" by the Tent of Meeting with Joshua. God too sets out to provide for a transition from Moses, and His vision both reflects and departs from Moses'. The message at the Meeting is harsh: "Behold you will sleep with your fathers, and this people will rise up and go astray." For naught, Moses, desperate entreaties and plans to teach "the fear of God." Regardless of all teaching, the people will inevitably stray, like a fact of nature, like the sea will rush and the sky will rain. Nature itself, the earth and the heavens, will stand witness to this.

Continuity does not imply avoiding disaster. It is finding a way back after disaster. God, like Moses, appoints Joshua to lead the people. Yet Moses sees Joshua as a mirror of the people, who like them must be told to "be strength and take courage," who like them, is dominated by "fears": he will "come" with the people, not lead them. By contrast, God empowers Joshua, seeing him as the new leader, "standing" in place of Moses, the two of them side by side: "you will bring the people."

In a similar fashion, God also echoes Moses' need for writing, yet this is writing of a different kind. Moses focuses on recording "teaching / law" (torah), which would be entrusted to the national leadership of priests, Levites and elders. The teaching would be sounded out to the people, laid on their "ears" as they imbibe and listen. The act of reading and of listening is collective, God, by contrast, commands to "write for yourself this song, and teach it to the children of Israel, put it in their mouth." Not a "teaching/law" but a "poem"; not for the leadership, but for the people; not for passive listening, but for speaking; not for the collective, but for each individual. Just as He empowers Joshua, God empowers the people. Yet the purpose of this writing is different. It will not control the future, and make distant generations "fear God." Rather it will be a "witness," placing this history-that-will-inevitably-unfold within the specific context context of God's words. "Not [to] be forgotten from the mouth of your seed," it will shape the meaning of their experiences.

The chapter closes with the intertwining of both the human and divine vision of continuity. Joshua is appointed as leader to "bring" not to "come"--yet Moses strengthens him. Moses "writes the whole teaching / law to its completion" and gives it over to the leadership. Yet he also "writes the words of this song and teaches it to the children of Israel." Finally, Moses, as per his original vision, speaks into the "ears" of the assembled people. Yet this time, he calls heaven and earth as "witnesses." It is not simply a teaching, but an act of testimony.]

Wednesday, December 23, 2015

Deuteronomy: Chapter 30

[For full chapter, click here

This chapter brings together and closes the sequence of chapters dealing with the future covenant, with their attendant blessings and curses. As such, it repeats and intensifies many of the key words that have run throughout these chapters: "Look, I have set before you to do the life and the good, and the death and the evil. Choose life that you might live!" Once again, the focus on "seeing" (r'e'e), and on binary oppositions with a clear path running between; again, the focus on the wayward "heart" (lev); on what is given (n't'n); and on learning to hear.

Yet there is a profoundly different ambiance to this chapter of reconciliation than those previous chapters of threat and imprecation. A kind of peace that comes after the storm: "and it shall be when all these things have come upon you, the blessing at the curse." No more dire warnings. It will all happen, regardless. What is important is that there is a way back. Again and again, the chapter repeats the root sh'a'v--"return," "reconciliation," which is also the root for the Hebrew word for repentance, teshuva: "you shall return (ve-shavta) to God, your Lord... and God your Lord will return (shav) you from captivity (shvut'kha)" . If in previous chapters, the land becomes a physical embodiment of the relationship with God, here the return to the Land is the direct correlation of spiritual reconciliation.

The focus on return is echoed in the literary form, which forms a chiastic frame structure, that returns us to the the initial threats and promises: if in chapter 28, the curse revolves around the "the fruit of your womb and the fruit of your animal," here, God will increase "the fruit of the womb at the fruit of your animal" more than it was in the beginning.

What is discovered in this long way home is that the way back was no so far as what it seemed. It is not in the heavens, or over the see, but "it is very close to you, in your mouth and your heart to do." What is furthest in the end turns out to be closest, like the frame structure of the chapter, which brings us back to the beginning.]

.

Sunday, December 20, 2015

Deuteronomy 29: In Writing

I was yours before I was me

If you move,

from root to tip

ash and sulphur

who will know me?

Thursday, December 17, 2015

Deuteronomy: Chapter 29

Tuesday, December 15, 2015

Deuteronomy 28: In Writing

Sunday, December 13, 2015

Deuteronomy: Chapter 28

split down the middle

a path running between

What will come on you?

Where the center cannot hold?

Wednesday, December 2, 2015

Deuteronomy 27: In Writing

cover.

tread hard

tread heavy

grip like a chisels

your arrival a hammer.

your veins a river

your bones the stones

your breath the wind

your voice runs within

like streams

like seeds

like the veins in the stones

waiting to be freed

if you listen hard enough.

Every mountain can bear witness

Let the weight of being

press into soil

that cradles and demands answer.

Say Yes to your blood

Say Yes to your shadow

Say Yes to sinews and muscles and bone

Say Yes to curse

say Yes to darkness

Say Yes to fractures

to caverns your cannot cross

Yes to before

Yes to after

Yes to the sea and the mountain and divide

And yes, the bounds are deep

And yes, I will gather

And yes I will bring

And yes and yes and yes.