Wednesday, June 12, 2024

Judges: Chapter 3

Sunday, June 9, 2024

Judges: Chapter 2

Friday, June 7, 2024

Judges: Chapter 1

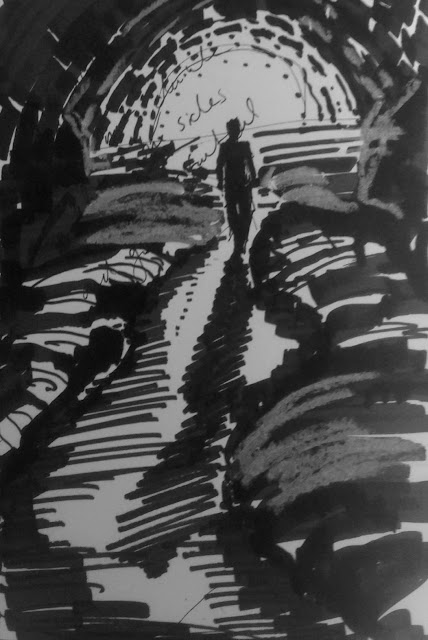

Start the after

we go up, we go down

jostled together.

Give me your blessing!

All we don't have

pressing against us

unwanted intimacy

lodged in our throat

as we spin, again and again.

[For full chapter, click here

The chapter begins "after the death of Joshua."It is both a continuation and a reprise, revisiting events that took place in the era of Joshua to create a bridge into this new reality. It is indeed a new reality of leadership, and the transformation is made apparent almost immediately. "Who shall go up for us initially, to fight the Cannanites?" (Judges 1: 1) the nation asks, searching for a new leader. ""Judah shall go up" (1:2) God answers, shifting the focus from individual to tribe. Relationships have now become fraternal rather than hierarchal ("Judah said to his brother"), as leadership disseminates within the tribal structure. Key events of the story of Joshua are retold within this new framework: the story of the conquest of Hebron the story of the conquest of Hebron is retold, yet this time with the focus on Judah, rather than the heroic Caleb. Here, it is the tribe that grants Caleb his inheritance, rather than the man who leads the tribe. as the leader is subsumed within his tribe. Only one individual still is given a central place: Otniel ben Knaz, conquerer of Debir, who fairytale-like, is granted Ahsa as his wife, in a passage is lifted almost verbatim from the account in Joshua. As in Joshua, Ahsa demands a "blessing" of her father, in the only piece of individual dialogue, and is granted the "upper and lower waters".

The reprise of the list of conquered and unconquered areas builds a precarious bridge to a new, dangerous era. The list of conquests is matched by a negative list of "not conquest", as the Canaanites "are resolved to dwell in that land" (1: 27). Even when the sons of Joseph manage to conquer Luz, they are haunted by a negative shadow of Luz, created by the Cannanites that left: "and the man named the city Luz, which is its name to this very day" (1:26). Rather than a triumphant settlement of the "land resting from war" that is the refrain of Joshua, we are presented with a tension-filled subjugation and uneasy coexistence. At the closing of the chapter, the negative refrain of "did not inherit" (lo horish) turns into active dispossession, as the tribe of Dan is driven off its land and into the mountains. Is this what will happen to all?

Monday, May 27, 2024

A Belated Goodbye to Joshua

It feels strange to say “Goodbye to Joshua” when I have just said a new “hello.”

After

several years (!), I can't even begin to understand or explain what made me stop the Joshua section one chapter before completion.

I

do remember after the end of Deuteronomy, I felt like I had reached closure, a

natural stop point. Joshua always felt like a tag-along, an added experiment. I

experienced the Book of Joshua as a comedown after the high poetry and complex

narratology of Deuteronomy—the language mundane, the violence off-putting. And

as a first-time new mother, I also had other concerns that felt more urgent. Yet

why I stopped right before the end, I can’t say. No doubt there were some deep,

unacknowledged currents there. I do know that the longer I waited, the more

distant I felt from the project, and the harder it became to go back. Finally I

blocked it out. A niggling untied end that I refused to consider.

Then came this year’s terrible Simchat Torah and its aftermath. As October turned to

November, November to December, month after month, the war raging on with no exit

point, I found myself completely blocked. Words disappeared. When I tried to draw, I had to push against

the intractable weight of futility. It was as bad—worse—as the block that started me on the Bibliodraw project so many years ago. This time I didn’t have

whiplash or amnesia. My arm was working. It was my heart that wasn’t. I found myself

desperate for a daily project. And the only project that seemed real enough and

urgent enough to matter was Bibliodraw—a project in which I had already

invested so much, a project embodying so many layers and history. It is also a project that gives me a framework

of feeling my way through this desperate time. Feeling my way, as I always have,

with the “tikvat hut ha-shani”, Rahab’s guiding bright thread of central

archetypal narratives. Returning to Bibliodraw is returning to the questions:

what are we doing here? How do we earn this home? How do we lose it? A project

that could engage my heart and intellect and hand as one.

Finding

a quiet moment does not happen often with four little kids in war time. But I suddenly

had a day when I woke up, and all my children were in childcare, and I had no urgent

projects that I needed to complete. For the first time in what seemed like months,

I drew a deep breath. And I said: I'm going to finish this. I will at least

complete Joshua, and close this one circle. Tie up this one dangling thread.

Because,

despite all my denials, it was still bothering me. The notebook there, sitting

in my closet, incomplete. And so I spent my quiet day reading through Joshua

again. This is a much more condensed process that my other “goodbyes”, which

were the slow accumulation of weeks' worth of ruminations and thoughts. This

rather is the result of months of studying, years of silence, then a quick one-day

review

So,

the those thoughts after this review.

The

Book of Joshua opens with a promise and a charge: I will be with you like I was

with Moses, but you must take courage and be strong. The book indeed continues

directly from the story of Moses, providing a bridge from Deuteronomy, . Yet it

also actively redoes Moses’ legacy in a complex balancing act. Jooshua’sleadership begins with crossing the Jordan, in a conscious recreation of the parting of the Red Sea. This places him

in the position of Moses, even as it rebirths Israel yet again as a nation. This

is a new generation, with a new destiny.

Israel then camps in Gilgal, where they recreate the Exodus, celebrating Passover. It

is a place of renewed literal brit, reactivating circumcision after the years

of wandering: “Make thee knives of flint, and circumcise again the children of

Israel the second time. … them [the children born in the desert] did Joshua

circumcise; for they were uncircumcised, because they had not been circumcised

by the way.” The desert era is seen as a hiatus, a kind of suspended animation

between the beginning of the journey and its end. It is only now, when the

children of Israel camp in Gilgal that they start national life anew

The ideas originally presented by Moses in the desert, which existed

until this point only in words and concept, are now put into action, finding embodiment

in the concrete space of the Land: cities of refuge, covenants in specific

places, words literally etched in stone. Yet embodiment is a dynamic and gradual process. Ideas become real, but

not at once. Repetition and variation are key elements as this book. We keep

going back to revisit history, even as we move forward. There is aonstant tension between potential and actual, becoming and being. The virtual desert

journey does not truly end.

Again and

again the verses declare that the conquest is complete, that the land is “subdued”,

that Israel is settled and secure. Again and again, we find that it is not so.

The same cities are conquered and unconquered, again and again: Hebron,

Debir. This tension is perfectly encapsulated at the end of the era, when

Joshua sends out representatives of eeach of the tribes to scout out and demarcatethe boundaries of their estate (18: 4). The land is then “distributed…each to

his inheritance” (19:49), and they make “and end of dividing the land’ (19:

51), even though, as we find out, the land is as yet mostly unconquered, and

not yet theirs to divide. The inheritance “ends” in abstracted visualization, even

as in concrete terms it remains undone.

Throughout

this intense period of process, Gilgal is the home base, from which Israel sets

out in short sorties, returning back to this space of covenant, as they try to

work out the relationship between themselves and God.

The

conquest begins with thedivine battle at with Jericho, which is essentially a version

of the Jubilee (yovel): seven cycles on the seventh day, which ends with

the blowing of the shofar (yovel), in a recreation of the Jubilee

opening which undoes human ownership. With the blowing of the Jubilee horn, all

the land returns to the owners originally allotted by God, all debts are

cancelled, human possession and transactions are undone. We return to origin. Just so, Israel’s inheritance

of the land begins with God announcing a Jubilee, undoing the ownership of the Canaanites.

The yovel is blown, the land returns to God. The victory is not the people’s

,but completely herem—forbidden, within the realm of the divine.

The

second battle with Ai opens the door for human involvement in battle, as God

steps back, acting mostly as tactician. And throughout the book, Joshua pushing

for greater and greater human involvement. “You are a great people, who have

great power…you shall drive out the Canaanites” (17:17), he tells the children

of Joseph, urging them to take charge of their inheritance.

Sunday, May 26, 2024

Joshua: Chapter 24

God of faithfulness and choice

He is your belonging

in a land not your own

and the cycles close

Monday, May 7, 2018

Joshua: Chapter 23

Friday, February 2, 2018

Joshua: Chapter 20

Wednesday, January 31, 2018

Joshua 19: In Writing

Walk, measure, name.

What do I see when I see you

turn, twist, hit, rise, drop,

leave and then return?

Sarid, I call you, remnant of a dream.

Sheva, satiation. Water welling. Where I swear, trust me,

what is born, what will be born, what God will bear

Molada, be my moledet, birthplace I fled, birthplace

that calls.

Be body, be belly, a place I can sleep,

the navel I came from, to which I am linked.

House of bread, house of sun,

springs of red and white,

water sharp as steel, sweet as fruit.

Mishal, what I ask for. Amiad.

Broad of shoulder, full of breath,

An ever receding sky, afek, afek.

Over there, at the hight, Ramah.

Thursday, January 11, 2018

Joshua: Chapter 19

Monday, December 25, 2017

Joshua 18: In Writing

crumble of soil between your toes

jab of rock against your heel

grit rubbing against your skin.

Watch the trail that stretches away behind you

Shadowy hillocks,

five toed valleys

marking you passgae

from here to there

from where you came to where you go

gaze beyond the horizon

Looking out

the land is filmed

over with the letters of your name.

textured with your skin's veins.

Sunday, December 24, 2017

Joshua: Chapter 18

Friday, December 15, 2017

Joshua: Chapter 17

Sunday, December 10, 2017

Joshua: Chapter 16

Saturday, December 9, 2017

Joshua: Chapter 15

Friday, December 1, 2017

Yehoshua: Chapter 13

Sunday, November 19, 2017

Joshua: Chapter 12

Monday, October 19, 2015

Deuteronomy: Chapter 21

At the closing of the chapter, the focus on seeing shifts to a focus on hearing, as the breakdown of relationship between parents and children is defined by "he does not listen to us" (21: 20); and the son's death penalty is supposed to make "all of Israel listen." Here, what is closest is expunged, as the parents "take out" (ho-tzi-u) their son to the court.

There is constant pulsation between bringing in and going out, between closing the senses, and opening them.]

Monday, September 21, 2015

Deuteronomy: Chapter 19

[For full chapter, click here

This chapter continues expanding up the key words that appeared in the previous one: k'r'v--within, amongs; d'r'sh, investigate, analyze. Now, two new leitworts enters: g'v'l--boundary, border; and d'r'kh--path, road. We at last speak of the definitive boundaries that create the sacred space "within" and the roads that form the interconnections. These preservation of these boundaries requires taking responsibility on the most primal level: a care for spilled "blood," for perjury, and a constant maintenance of the sacred space within: "you must burn out the the clean blood within" in a continuous re-calibration. There must be a "redeemer of the blood" (go'el ha-dam). Even if inadvertent, any act of killing is "murder" and demands a complex play of redemption and refuge.

The return to Sinai in the previous chapter also returns us to the laws given in the aftermath of Sinai: "He that hits a man and dies shall be put to death; but if he did not lie in wait, but God brought it to his hand, I shall appoint a place where he shall flee" (Exodus 21: 12-13). These laws are reiterated in this chapter, but now grounded in the earth "which you are about to enter." Characteristically for Deuteronomy, the laws are now focused on humanity rather than on God: "designate for yourself three cities within your land."

And it is only in taking this responsibility that the land will truly become "yours." The chapter open by emphasizing that the land does not yet truly belong to Israel: "when God shall cut off the nations whose land God your Lord is giving to you...and you dwell in their cities and in their houses." Only after taking responsibility for inadvertent murder does that land become Israel's: "You shall separate three cities in the midst of your land, which God gave you to posses."

In taking this responsibility, one can even change and move the seemingly immutable outer boundary. Boundaries are perhaps absolute on a personal level-- "do not encroach on the boundary of your brother, which the early ones have bound"--but on a national level, the are flexible, expanding to fit the nation's commitments: ": "If God your Lord expand your border...designate another three cities of refuge." ]