It

feels strange to say “Goodbye to Joshua” when I have just said a new “hello.”

After

several years (!), I can't even begin to understand or explain what made me stop the Joshua section one chapter before completion.

I

do remember after the end of Deuteronomy, I felt like I had reached closure, a

natural stop point. Joshua always felt like a tag-along, an added experiment. I

experienced the Book of Joshua as a comedown after the high poetry and complex

narratology of Deuteronomy—the language mundane, the violence off-putting. And

as a first-time new mother, I also had other concerns that felt more urgent. Yet

why I stopped right before the end, I can’t say. No doubt there were some deep,

unacknowledged currents there. I do know that the longer I waited, the more

distant I felt from the project, and the harder it became to go back. Finally I

blocked it out. A niggling untied end that I refused to consider.

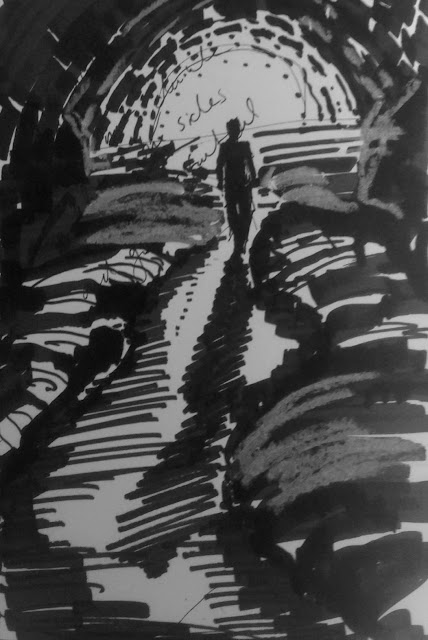

Then came this year’s terrible Simchat Torah and its aftermath. As October turned to

November, November to December, month after month, the war raging on with no exit

point, I found myself completely blocked. Words disappeared. When I tried to draw, I had to push against

the intractable weight of futility. It was as bad—worse—as the block that started me on the Bibliodraw project so many years ago. This time I didn’t have

whiplash or amnesia. My arm was working. It was my heart that wasn’t. I found myself

desperate for a daily project. And the only project that seemed real enough and

urgent enough to matter was Bibliodraw—a project in which I had already

invested so much, a project embodying so many layers and history. It is also a project that gives me a framework

of feeling my way through this desperate time. Feeling my way, as I always have,

with the “tikvat hut ha-shani”, Rahab’s guiding bright thread of central

archetypal narratives. Returning to Bibliodraw is returning to the questions:

what are we doing here? How do we earn this home? How do we lose it? A project

that could engage my heart and intellect and hand as one.

Finding

a quiet moment does not happen often with four little kids in war time. But I suddenly

had a day when I woke up, and all my children were in childcare, and I had no urgent

projects that I needed to complete. For the first time in what seemed like months,

I drew a deep breath. And I said: I'm going to finish this. I will at least

complete Joshua, and close this one circle. Tie up this one dangling thread.

Because,

despite all my denials, it was still bothering me. The notebook there, sitting

in my closet, incomplete. And so I spent my quiet day reading through Joshua

again. This is a much more condensed process that my other “goodbyes”, which

were the slow accumulation of weeks' worth of ruminations and thoughts. This

rather is the result of months of studying, years of silence, then a quick one-day

review

So,

the those thoughts after this review.

The

Book of Joshua opens with a promise and a charge: I will be with you like I was

with Moses, but you must take courage and be strong. The book indeed continues

directly from the story of Moses, providing a bridge from Deuteronomy, . Yet it

also actively redoes Moses’ legacy in a complex balancing act. Jooshua’sleadership begins with crossing the Jordan, in a conscious recreation of the parting of the Red Sea. This places him

in the position of Moses, even as it rebirths Israel yet again as a nation. This

is a new generation, with a new destiny.

Israel then camps in Gilgal, where they recreate the Exodus, celebrating Passover. It

is a place of renewed literal brit, reactivating circumcision after the years

of wandering: “Make thee knives of flint, and circumcise again the children of

Israel the second time. … them [the children born in the desert] did Joshua

circumcise; for they were uncircumcised, because they had not been circumcised

by the way.” The desert era is seen as a hiatus, a kind of suspended animation

between the beginning of the journey and its end. It is only now, when the

children of Israel camp in Gilgal that they start national life anew

The ideas originally presented by Moses in the desert, which existed

until this point only in words and concept, are now put into action, finding embodiment

in the concrete space of the Land: cities of refuge, covenants in specific

places, words literally etched in stone. Yet embodiment is a dynamic and gradual process. Ideas become real, but

not at once. Repetition and variation are key elements as this book. We keep

going back to revisit history, even as we move forward. There is aonstant tension between potential and actual, becoming and being. The virtual desert

journey does not truly end.

Again and

again the verses declare that the conquest is complete, that the land is “subdued”,

that Israel is settled and secure. Again and again, we find that it is not so.

The same cities are conquered and unconquered, again and again: Hebron,

Debir. This tension is perfectly encapsulated at the end of the era, when

Joshua sends out representatives of eeach of the tribes to scout out and demarcatethe boundaries of their estate (18: 4). The land is then “distributed…each to

his inheritance” (19:49), and they make “and end of dividing the land’ (19:

51), even though, as we find out, the land is as yet mostly unconquered, and

not yet theirs to divide. The inheritance “ends” in abstracted visualization, even

as in concrete terms it remains undone.

Throughout

this intense period of process, Gilgal is the home base, from which Israel sets

out in short sorties, returning back to this space of covenant, as they try to

work out the relationship between themselves and God.

The

conquest begins with thedivine battle at with Jericho, which is essentially a version

of the Jubilee (yovel): seven cycles on the seventh day, which ends with

the blowing of the shofar (yovel), in a recreation of the Jubilee

opening which undoes human ownership. With the blowing of the Jubilee horn, all

the land returns to the owners originally allotted by God, all debts are

cancelled, human possession and transactions are undone. We return to origin. Just so, Israel’s inheritance

of the land begins with God announcing a Jubilee, undoing the ownership of the Canaanites.

The yovel is blown, the land returns to God. The victory is not the people’s

,but completely herem—forbidden, within the realm of the divine.

The

second battle with Ai opens the door for human involvement in battle, as God

steps back, acting mostly as tactician. And throughout the book, Joshua pushing

for greater and greater human involvement. “You are a great people, who have

great power…you shall drive out the Canaanites” (17:17), he tells the children

of Joseph, urging them to take charge of their inheritance.

Yet at the very closing, the book returns to its

opening point of yovel: the land is not truly theirs. It remains always God’s,

a gift that precludes true possession, always given, never had. It is the

process itself that is true belonging, the various points where God showed his faithfulness.

What remains is to make a choice, and witness your own commitment.