“And these are the names of the children of Israel who went

to Egypt with Jacob, each with his family… Joseph and all his brothers and all

that generation died, and the Israelites were exceedingly fruitful; they

multiplied greatly, and increased in numbers” Those opening verses set into

place the themes of the Book of Names (the Hebrew name of Exodus) as a whole.

We have moved from the primordial, archetypal Genesis, that deals with the

creation of the individual identity, of the self. Now we must find a name for

the nameless masses, the meaning of the self within the context of the many.

The book of Genesis deals with the “chronicles of Man as he

was being created.” It revolves around the interrelationship of the individual

with the world. Its central metaphor is hands: how do we handle and manipulate our environment.

The key repeating phrase is “ve-yishlach yado—to send forth the hand”: “And

now, lest he send forth his hand and eat from the tree of life” introduced the

exile from Eden; “Do not send forth your hand against the boy” closes the

demand for the sacrifice of Isaac; “I told you not to send forth your hand

against the youth” Reuben cries after the sale of Joseph. Letting go versus

holding on; learning how to relate to Other. The book revolves around ever-intensifying

painful relations between sibling and sibling, and man and woman: the two main

patterns of Otherness. It closes with Joseph’s acceptance of the wrong his

brothers have done him; balanced by Judah’s acceptance of the fact that Rachel—and

only Rachel—holds Jacob's heart. The self has learned to accept the independence

of other.

Exodus is the next stage. Having moved beyond the placement of

self within family (Genesis), we now

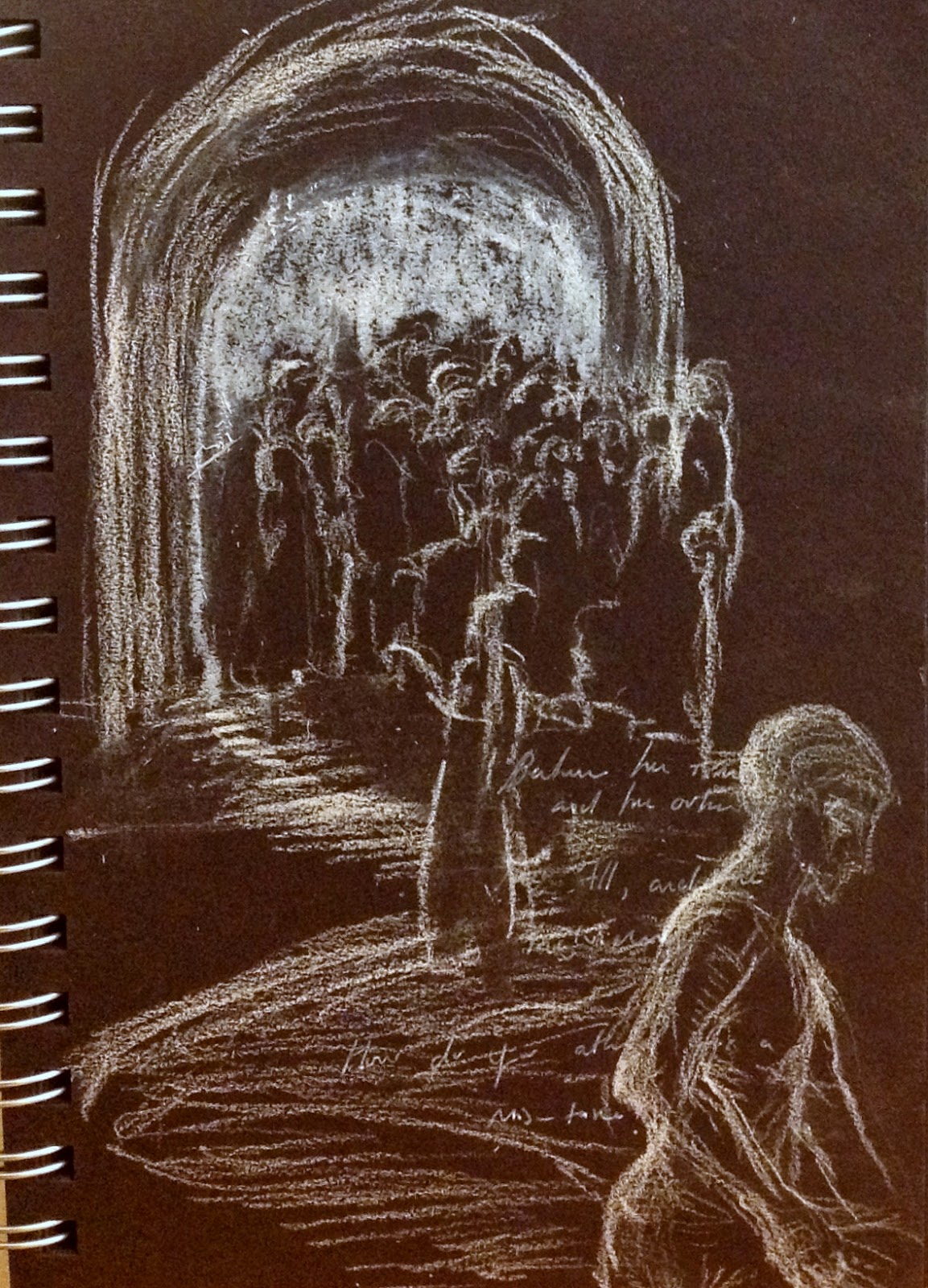

begin to deal with the birth of a nation. And it is a unique story of

nationhood that begins in being stripped of all elements of identity. This is

the faceless generation that has no land and has no name, birthing “like

animals.” It is a story of nationhood that begins in powerlessness.

Yet the painful

acceptance of otherness that introduces this story opens the possibility of a different

mode of identity. Not the certainty of power and choice, but relationship

to absolute Other—God. The key images of

this book are “eyes” and “ears”; to “see” “hear” “smell”: from a focus on the

hands, we move to a focus on the face. This is the book of learning to

communicate “face to face.” Moses, the liminal figure who is “drawn from the

waters” remaining always “on the banks” between heaven and earth ,God and man,

is central for this connection.

For it is not a simple process. Rather, it requires

transformations on both sides. “What shall I say Your name is?” Moses asks, and

God changes names within communication—from the impersonal “powers” (Elohim)

to the “Almighty power” (el shaddai) to the God of history who will “be

what He will be”, and who bears a personal

Name. Israel also is transformed, in a protracted year-long process. The Exodus

is dominated by birth-imagery: from the preternatural fecundity of the opening

chapter, to the bloody doorways that birth the nation, to the passage through

the waters that spits the despairing slaves out on the other side as a free people.

“My firstborn child, Israel” “opens the womb,” and all that “open the womb”,

whether human or animal, are consecrated. Birthing a child begins a process. The opening

of the womb of the Sea of Reeds is followed by the “testing” of the terrible twos: tantrums about food and attention, doubts about love.

The parent-child imagery becomes entwined with metaphors of

infatuation and young love (maybe they are not so far apart as we think…) Not

for nothing did the prophets describe the Exodus as “the grace of your youth,

the love of your bridal days. You followed Me through the wilderness, in an

untamed land.” The passage through the wilderness is a dance of approach and

retreat, closeness and distance. The lead-up to Sinai is accompanied by a

demand for greater and greater closeness, coupled with existential uncertainty:

“Is God amongst us or nothingness?” Again and again, God imposes boundaries,

which Israel “test”: “and they gazed upon God and ate and drank.” Yet consummation (both meanings) breeds not

certainty, but the need for distance and escape. The relationship is too

overbearing, a complete crushing of the self. “Speak you to us, but let not God

speak to us lest we die.” In the aftermath of Sinai, we begin the translation

of God to humanity, bringing God down to earth.

The creation of the Dwelling is a myse-en-abyme for the

book as a whole, a point-counterpoint of self and other, closeness and

distance, the accommodation (in both senses!) of God an humanity.

We begin with God’s “pattern,” his “command” to Moses. This is vision dominated

by the unified keruvim, locked together, but forever apart, each on a separate

side. This must pass through the prism of Bezalel, who will translate it into

physicality. Yet the translation of revelation into material brings a counter

movement from Israel, who rush in to create the Golden Calf—an attempt at

complete closeness, without the burden and threat of Other.

Moses once again steps into the breach.He brings God to acknowlege that “no man can see My face and live.” The relationship to

humanity must be slant, to the back, rather than direct revelation. Thus, He accedes

to Moses' request for forgiveness “You must walk within us.” God will indeed “be

what He will be,” revealed in the walking, in the process, rather than directly.

This opens a space for human action, and in the next

chapter, the people begin to build the Dwelling, transforming God’s vision with

their own desires and “hearts.” Moses stands at the center, uniting their disparate

parts back to the initial ideal that “he had seen on the mountain.”

The book closes when the pieces come together, and the

Dwelling suddenly ignites, “a pillar of fire by night.” There is a synergy in

the growth of a nation. In the end, the whole is greater than the sum of separate parts, greater than the individuals who dominated the Book of Genesis. Moses cannot even enter the

Dwelling that he created. This allows a new unity of God and humanity. Not the painful

separated unity of the keruvim, who are of “a single mass,” gazing at

each other, but divided by the breath of their wings. Rather, it is a unity that

comes of “walking together”: “when the

cloud rose, the people would rise and travel.” In the year that followed the birthing of the nation in the womb of Egypt, a new relationship has been built. "For the cloud of God dwelt above the Dwelling by day, and fire was over it by night, in the sight of all the house of Israel, throughout all their journeys." God and humanity journey together, within "sight" of each other, essentially unknown and Other, but fully present.

.JPG)